HAIR

Reviewed by Jeffrey R Smith of the San Francisco Bay Area Theatre Critics Circle

The Encinal Drama Department courageously explores the radical sixties via the American Tribal Lock-Rock Musical HAIR.

The musical visits the incubator of many cultural and political elements that we take for granted today: the anti-war and anti-draft movement, environmental protection, women’s rights, mysticism, broad based humanism, sexual liberation, tolerance and cultural pluralism.

These features of the American landscape were brought to you by the Hippies; a utopian subculture that looked beyond materialism for a vision of what we could become.

Diane Keaton was part of the 1968 Broadway cast of HAIR; strangely, to this day she reminds us that although she played a Hippy on stage, she was not a Hippy.

Remarkably, the Encinal production seems to capture the very essence of the Hippy movement; to the credit of Director Robert Moorhead, the show—despite the enormous cast—achieves an intimate cohesive feel, a harmonic convergence of creative spirit and enlightened hope; the unifying tribal force is palpable.

The rousing opening song, Aquarius, boldly led by Brazjea Willard-Johnson with an exuberant Tribal chorus, asserts that planet Earth is governed by a celestial clock—the precession of the equinoxes—and humanity is getting its wake-up call; peace, love and understanding are about to usurp the old evil gods of greed, war and hate.

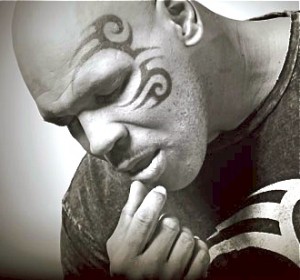

Just as the Christian era is believed to have been ushered in by a Virgin, the Aquarian Age too has its Madonna only in HAIR it is simply Donna and Berger—played marvelously by Darryl Williams—is desperately singing and searching for “my Donna.”

While drugs have been a part of the American experience since the Jamestown Colonists discovered the hallucinogenic properties of Jimson Weed, it was the sixties that brought on a proliferation of every “mind expanding” toxicant known to the recreational pharmacist and sorcerer; the song Hashish, performed by the Tribe in an eerie and trippy haunting howl, signals the audience that mystic revelation can spring from psychedelics much easier and quicker than yoga, asceticism and rigorous self-denial.

While the United States was busily bombing the Ho Chi Minh Trail and trumped-up body counts filled the evening news, the nation remained priggish about S E X; the song Sodomy drags words before the Klieg Lights that were hitherto only uttered in locker rooms, pajama parties, frat houses and confession booths; words like … like … well you know.

Woof—superbly played by the unassuming leading man of Encinal Theater, and Encinal’s West Point selectee, Raymond Cole-Machuca—lyrically runs through the entire Scortatory Dictionary trying to find the basis of its shock value.

Whether intentional or not, Raymond’s Woof is the oak tree about which the Tribe seems to hang its Teepee; he is both the Oberon and Puck of this musical.

Relentlessly threaded through the musical, submerging and reemerging repeatedly, is the problem of the Draft: compulsory military service; most likely in Vietnam.

The lead character, Claude, is inexorably ratcheted closer and closer to boot camp and the nightmare that lies beyond.

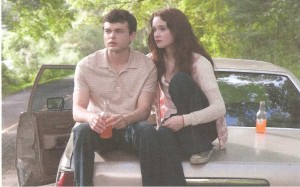

Claude—as played by Ryan Borashan is brilliant casting.

Ryan is an amazing young gentleman actor not to be under-estimated; he is so capable and expansive on stage that his own teachers have difficulty recognizing him.

Claude does his best to dismiss reality; he dives into a false identity in the song Manchester England as if to momentarily escape the Selective Service who has issued him a draft card.

Ryan’s rendering of the song betrays the desperation of a draft eligible teenager trying to suspend his sense of disbelief to buy one more day in protracted adolescence; neither his parents nor the Tribe fully comprehend the enormity of his crisis.

Later as reality begins to infiltrate Claude’s denial mechanism, Ryan wonderfully sings what is arguably the finest song of the show: Where Do I Go.

One of the most startling voices in HAIR is Kalyn Evans; when she chimes into the number Ain’t Got No, the song leaps a full octave qualitatively; this reviewer spent the rest of the evening anxiously waiting for an encore from Kalyn.

As previously stated, the environment was moved to the front burner by the Hippy Movement and the environmentalist in HAIR is the amply Pregnant Jeanie—played by very talented Miss Ruby Wagner.

Miss Wagner—one of the bright beacons in this show—perhaps acceding that there were vagaries in the sound system, not only sang mellifluously, but she communicated her song, Air, to the audience with expression, articulation and earnestness while never compromising on melody.

In a subjective debate over the virtues of Black Boys versus White Boys and in a nod to Motown and Phil Spector, Emani Pollard, Kalyn Evans and Jayla Velasquez delightfully shimmied in shimmering minis.

Costuming and make-up deserve major kudos.

Initially one might think this is a parody of the sixties until one realizes that this is how it really was, equally audacious and outrageous in the sixties as it is on the Encinal Stage.

To connect or reconnect to a time when expectation and hope trumped the status quo and the military-industrial complex, get thee to HAIR.

The show runs through Saturday March 23 and should not be missed.

Period dressing is encouraged.

Call Encinal High at 748-4023 for more details.