MARIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS

THE WHIPPING MAN

by Matthew Lopez

Directed by Jasson Minadakis

Starring L. Peter Callender, Nicholas Pelczar and Tobie Windham

The people made worse off by slavery

Were those who were enslaved.

Thomas Sowell

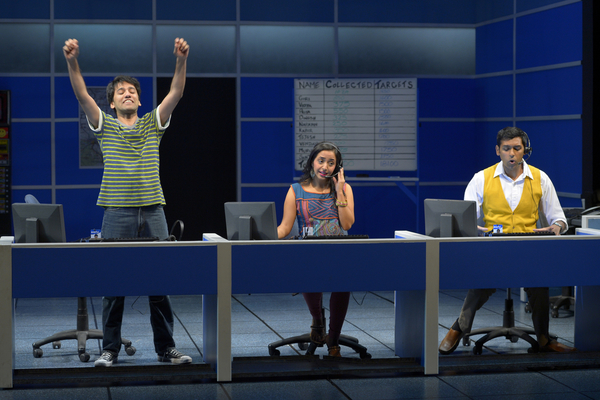

Marin Theatre consistently gives us exceptional productions and Jasson Minadakis is without equal as a director. Any production he touches becomes thought provoking, meaningful theater at its best. THE WHIPPING MAN is no exception. “Set a week after the fall of Richmond at the end of the Civil War and spanning the date of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, THE WHIPPING MAN explores a moment in our history when everything changed and anything seemed, and perhaps actually was, possible,” says Minadakis. “Matthew explores how faith is one of the strongest ways to build family and community and to honor history…..….Faith in ourselves, our family and friends, our community or a divine power is the light that parts the darkness.”

The faith in this play is Judaism. When the Southern Aristocracy owned slaves, those people became a part of their family. Although they were possessions, they were still expected to follow the moral constructs of the people who owned them. Simon (L. Peter Callender) and John (Tobie Windham) are Jewish. They belonged to Caleb’s (Nicholas Pelczar) family. The play opens in Caleb’s now almost destroyed home in Richmond, Virginia in 1865 on a Friday night during the Jewish Passover. It is important to understand the Jewish humanistic philosophy when you watch this play because it colors each characters reaction to one another. Jewish law forbids unethical treatment of slaves and encourages owners to make them part of the family. They were forbidden to physically abuse their slaves or to sell them to harsh masters.

And yet, these people were property and no matter how well meaning the master was, there were moments when he fell from grace. In this play Caleb’s father who was portrayed as a kind, humane man beat both Simon and John, and violated Simon’s wife. Caleb was overbearing and cruel to John even though the two grew up together as brothers. As Simon explains, ”You did it because you could.”

Caleb disillusioned by the cruelty and bloodshed of the war has abandoned his faith. “I stopped believing. It’s as simple as that,” he tells Simon. And Simon who still believes there is a higher power to protect them all says, “God doesn’t like fair weather friends. “ He continues, ”You don’t lose your faith by stopping believing; you lose your faith by not asking questions.”

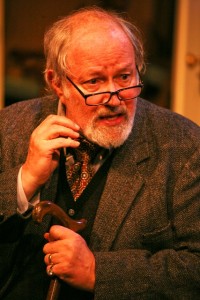

As the play develops, we are asked to question where justice begins and why men abandon their sense of humanity when they have power over another. The acting in this play is nothing short of amazing. L Peter Callender is a supreme artist and anyone who has the privilege of seeing him perform on stage knows he is unforgettable in any part he plays. He outdoes himself in this play. He carries the action and he is breathtaking every moment he is on that stage. Tobie Windham is perfect as the rebellious angry brother and Caleb is right on the mark as the disillusioned son of a Jewish plantation owner who finally sees how little help his faith was to him when faced with impossible choices not just on the battlefield but in a home where people were subjugated to humiliation because they were owned.

The production is a masterpiece on every level and we have Jasson Minadakis to thank for that. He is both the director of this fine and memorable piece of theater and artistic director of the theater. One can wax eloquent about the set, the lighting and the action…but there are no words to substitute seeing the play for yourself. It is far more that a work of fiction on a stage. It is a reflection of what life means and how we can all try to live it with honor and dignity.

Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery,

I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

THE WHIPPING MAN continues until April 21, 2013

Marin Theatre Company

397 Miller Avenue

Mill Valley, CA 94941

415 388 5208

www.marintheatre.org