By Judy Richter

The title character in “And Miss Reardon Drinks a Little” does indeed drink, not just a little but a lot.

That’s apparent in the opening moments at Dragon Theatre in Redwood City as Catherine Reardon (Sheila Ellam) pours two bottles of alcohol into an ice bucket, briefly holds a third (presumably vermouth) over it, and then fills a tumbler for herself.

She refreshes that drink throughout Paul Zindel’s two-act play as rancor and craziness fill the apartment that she shares with her younger sister, Anna (Lessa Bouchard).

Soon to join Catherine and Anna for dinner in their late mother’s apartment is their married sister, Ceil Adams (Kelly Rinehart). Ceil, the superintendent of a Staten Islandschool district, wants to persuade Catherine, an assistant principal in that district, to have Anna committed to a mental hospital.

Anna, who teaches high school chemistry in the same district, has been deteriorating emotionally ever since she and Catherine traveled to Italy, where Anna was bitten by a stray cat. Despite evidence to the contrary, Anna believes that she contracted rabies from the bite.

Her irrational behavior has recently led her into an inappropriate encounter with a male student.

Anna also has become a vegetarian, making zucchini and fruit smoothies the dietary staples for both herself and Catherine. In fact, Anna abhors all animal products, leading her to shriek and jump onto the sofa when she sees them.

Those reactions are caused by the unexpected arrival of Fleur Stein (Mary Lou Torre), a guidance counselor at Anna’s school, and her husband, Bob (Kyle Wood). Anna first sees Fleur’s fur wrap, followed by the fur-lined leather gloves that Anna’s colleagues have given her as a get-well gift.

Repeatedly ignoring hints and then requests that they leave, Fleur and Bob bicker with each other and with the sisters.

The couple become so obnoxious that they trigger a rare display of unity among the sisters, who gleefully forgo their sibling rivalry and come up with an extreme way to get the invaders to go.

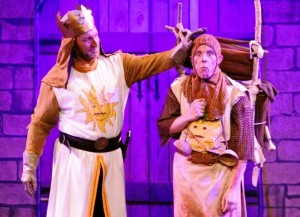

While Ellam’s sarcastic Catherine is casually neat, Bouchard’s Anna — her long, red curls unfettered — is disheveled.

Ceil is a stark contrast to both with her tailored business suit (costumes by Kimberly Davis), prim hair style and no-nonsense glasses. Her attire reflects her uptight persona. Her sisters’ outfits are similarly reflective of what they’re like.

Because it’s a dark comedy with generally unlikable characters and themes, “Miss Reardon” requires skillful directing and acting to bring out subtleties.

In this case, director Shareen Merriam and her cast fall short of that goal, resulting in mostly one-dimensional characters and emotional excesses leading to screaming matches. On the other hand, this play is not as well written as Zindel’s earlier Pulitzer- and Obie-winner, “The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds.”

‘Miss Reardon’ will continue at Dragon Theatre, 2120 Broadway St., Redwood City, through Sept. 22. For tickets and information, call (650) 493-2006 or visit www.dragonproductions.net.