Woody’s [rating:3.5]

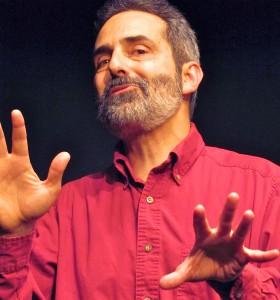

Marcus Shelby skipped the hat and wore less conspicuous shoes for his Cal Performances tribute to Duke Ellington. Courtesy photo.

To be inventive or not to be inventive, that is the question.

When it’s bandleader-bassist Marcus Shelby doing the asking (as well as the innovating), the answer is a resounding “yes.”

In a Cal Performances concert at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley celebrating Duke Ellington’s 115th birthday, Shelby flaunted his calculated risk of failing — by juxtaposing swinging big-band jazz and Shakespeare.

He didn’t fail.

Instead, he and his 15-member, mostly-brass ensemble evoked toe tapping, applause, whistling, cheers and foot stomping with each section of the obscure but stimulating “Such Sweet Thunder.”

The suite had been popularized by the Duke on vinyl but written by his longtime collaborator, Billy Strayhorn.

Shelby’s sidemen brought out each segment’s uniqueness, helping me see how Strayhorn was in effect trying to cover the entire jazz landscape in a single symphonic work.

And each segment’s pithiness left me wanting more.

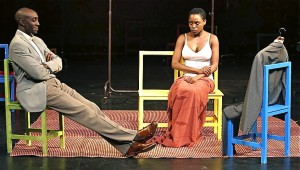

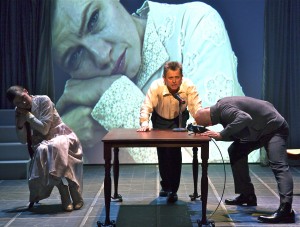

Because the music was based on the plays and sonnets of the Bard, it was a big deal but not a big surprise that Shelby integrated soliloquys by five actors from Cal Shakes, more formally known as the California Shakespeare Theater.

While all the spoken-word interludes were top-notch, I found some connections to the music tangential at best and, thereby, hard to distinguish — even given information that “the essence” of Shakespeare’s material was being emphasized rather than any one scene or character.

I did find a few links clear-cut, though.

A Juliet balcony scene obviously bonded with a ballad, “The Star-Crossed Lovers,” and a bluesy waltz-time “Lady Mac” danced a direct path to “Lady Macbeth.”

“Sonnet to Hank Cinq” was, of course, a hip reference to Henry V, and “Sonnet for Sister Kate” might have had a little to do with Willie the Shakes’ “Taming of the Shrew.”

In my mind’s eye, by evening’s end I’d labeled the experiment fascinating and a success.

Even though I’d have liked the music alone.

The pre-intermission set of the concert, which also marked the 15th year of the Shelby group and the 40th anniversary of Ellington’s death, consisted of more familiar melodies.

It was dubbed “The Legacy of Duke Ellington: 50 Years of Swing!”

And swing it did.

For me, the highlight was an unbilled rendition of “Take the ‘A’ Train,” but I was also delighted by “Perdido,” the show’s bouncy opener; “C Jam Blues,” its rousing closer; and “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” and “Hit Me With a Hot Note” in the middle.

The San Francisco-based Shelby, who took only one solo, happily spotlighted other musicians from his troupe as well as his guest stars.

Into the latter category fell scat vocalist Faye Carol (the high-strutting, scat-singing “Queen Bee” who’s worked with Shelby for 20 years), violinist Matthew Szemela (who occasionally kept time with both feet at the same time), sax vet Jules Broussard (whom the bandleader labeled one of his mentors) and trumpeter Joel Behrman.

Perfection was elusive, however.

I couldn’t appreciate a trumpet solo despite Shelby’s explanation that some of its notes were un-trumpet-like.

And I cringed when Carol grew raspy several times on “In My Solitude.”

Duke Ellington composed almost 1,000 pieces of music. The concert only skimmed the proverbial surface. But it did provide a glimpse into the man’s genius — through an exciting evening of standard and not-at-all-standard jazz.

In case you missed the Shelby orchestra, Cal Performances offers other excellent jazz choices. Try, for example, vocalist Mavis Staples on Oct. 30, Irvin Mayfield and the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra on Nov. 16, the Peter Nero Trio (playing Gershwin compositions) on Feb. 8, Cassandra Wilson (singing Billie Holiday tunes), or pianists Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock on March 19. Information: www.calperfs.berkeley.edu/buy/ or : (510) 642-9988.