Woody’s [rating:4.5]

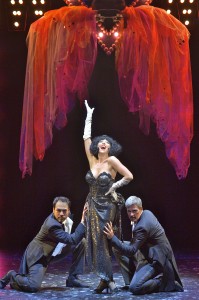

Her two dancing boy-toys, Michael Balderrama (left) and Bob Gaynor, flank Meow Meow at Berkeley Rep. Photo, courtesy kevinberne.com.

Expect the unexpected.

And Meow Meow, leggy brunette bombshell and mock diva, will energetically provide it at the Berkeley Rep.

She’s fabulous — in all meanings of the word: mega-excellent; larger than life-sized; and a spectacular invention, in the fabled sense.

She’s half wildcat, half wild card.

With ersatz desperation, the combo singer-comedian-actress-dancer weaves her innate talents and cleverness into a triumphant 90-minute patchwork-quilt, musical-spoof that’s headed for Broadway.

She also parades as a wannabe revolutionary and philosopher (“Is there a God?”).

But her main shtick is to pull male theatergoers onstage and womanhandle them during “An Audience with Meow Meow,” a title with multiple interpretations.

Not for a second did I envy folks dragged from the front rows to paw her legs, grope her torso and act as comedic chairs and foils.

But those repeated gambits, albeit somewhat cheesy, are extremely funny.

Meow Meow — whose given name is the slightly less glamorous Melissa Madden Gray — along the way dices and slices diva and cabaret mythology, turning theatrical clichés sideways and upside down.

She revels in taking risks.

She satirizes superstars who thrive on flowers tossed at them, who physically toss themselves onto their fans, who praise to the rafters whatever venue they’re in.

With hints of, and homages to, Marlene Dietrich, Edith Piaf and Lady Gaga.

And I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn she’d secretly viewed re-runs of Carol Burnett and Lucille Ball’s televised physical antics.

Or been addicted to the black-and-white slapstick of Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton.

Meow Meow, who as a small girl wanted to be a ballerina but ended up getting a law degree instead, isn’t above making cabaret standards her own.

She particularly excels with Jacques Brel melodies and Harry Warren’s “Boulevard of Broken Dreams.”

But the show-stopper becomes an antique Bobby Darin novelty hit, “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini,” with which she lampoons genre after genre after genre.

Her being exceptionally limber, agile and gymnastic also allows a self-serving self-reflection: “Is art a woman killing herself?”

Meow Meow says she especially loves entertaining audiences who’ve grown tired of green witches, jukebox musicals and singing Mormons.

I’d say the entire opening night crowd — including me — fully appreciated her creative efforts in that regard.

A multi-lingual international star (she’s been a headliner in Berlin, Sydney and Shanghai), she was ably supported by two boy-toy dancers, a four-piece band and a white-mouse puppet.

And competently directed by Kneehigh Theatre’s Emma Rice, previously represented winningly at the Rep by “The Wild Bride” and “Tristan & Yseult.”

Meow Meow, whose fame skyrocketed while performing in Michel Legrand’s “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” in London in 2011, slyly tries to be mysterious and cloak her origins, purposefully referring both to Moscow and Berlin.

But she’s really an Aussie.

I couldn’t determine, however, if she adopted her stage name before or after meow meow, the street drug, gained popularity. Mephedrone, that potent designer amphetamine, has become a British rave favorite because it produces effects parallel to cocaine and ecstasy.

Meow Meow, the performer who’s also credited with writing her show, supplies a public wave of ecstasy as an alternative.

Consequently, I might hate myself in the morning for using what may be a cat-astrophic ending, but I really can’t stop myself (she instantly turned me into a fan, you see):

Meow Meow’s act may not reach purr-fection, but it does come as close as a whisker.

“An Audience with Meow Meow” plays at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre‘s Roda Theatre, 2015 Addison St., Berkeley, through Oct. 19. Night performances Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, 8 p.m.; Wednesdays and Sundays, 7 p.m.; matinees, Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays, 2 p.m. Tickets: $14.50 to $89, subject to change, (510) 647-2949 or www.berkeleyrep.org.