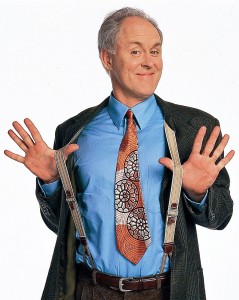

Dave Getz and I were relaxing on a stone bench outside Peet’s in San Anselmo’s Red Hill Shopping Center some time ago.

My friend sported his usual: a baseball cap, a mischievous smile and twinkling hazel eyes. He was so excited chatting about his new passion that an hour and a half had zoomed by before we realize our butts ached.

To a stranger, Dave might be an anomaly.

The public face of the longtime drummer for Big Brother and the Holding Company, legendary rock ‘n’ roll group, isn’t sensitivity, introspection and judiciously selected phrases.

But they’re familiar to any who know him.

That afternoon, however, his words reverberated with passion, like quivering cymbals. He was talking about premiering his original melodies instead of replicating those popularized by Janis Joplin.

And he did it, following through with a Global Recording Artists album titled “Can’t Be the Only One” — which also happens to be the name of its lead track, which features Dave’s music and previously unheard lyrics by Joplin.

The CD’s available at WWW.gragroup.com and www.cdbaby.com.

Not so long ago, over lunch on the deck of a Thai restaurant in Larkspur, I listened one more once — to a new jump-start of excitement. Dave again sported a baseball cap, a mischievous smile and twinkling hazel eyes.

The “consummate sideman,” as the Fairfax resident has called himself, had been thinking about a fresh CD — featuring the balafon, a West African instrument that looks like a xylophone made of gourds but plays an uncommon five-note pentatonic scale.

“No one has an album that’ll sound like this!” he exclaimed, his words once again reverberating with passion.

In addition to some traditional African melodies, he planned — and, in fact, is still planning — updates on some antique tunes such as “Buttons and Bows,” an Oscar-winning pop song that appeared in a Bob Hope film of the ‘40s, “The Paleface,”

Dave has long possessed the instrument, but it just as long was relegated to his home — until he showcased it at a Fairfax Library opening of an exhibit featuring the montages of, yes, Dave Getz, fine artist.

Since then, his schedule continually has been overcrowded with gigs, so he had to delay the CD.

Release date: Still undetermined, despite several tracks having been completed.

When it finally comes out, listeners can expect a revelation.

Not unlike the revelation they experienced with “Can’t Be the Only One,” which, just as he had imagined it, became a “progressive, world mix — a little jazz, a little rock, elements of African, some funk.”

All “rhythm-driven.”

I’d chuckled when he’d first used that phrase. What else could anyone expect from the drum guy?

As the sun had bounced off Dave’s white hair and white van dyke back then, I could almost feel his mind racing, hurdling all the simultaneous details required to arrange rehearsals, dodge financial perils and draw an in-person crowd for the debut of The Dave Getz Breakaway.

He had grinned broadly as he told me about the players, who turned out to include Tom Finch on guitar; Peter Penhallow on keyboards; Kate Russo on violin; Chris Collins on guitar; John Evans and Peter Albin on bass; and James Gurley on guitar.

Dave, naturally, was the drummer.

The new group’s lead singer was Kathi MacDonald, a blues diva who died a short time later.

I’d been attentive as Dave painted word-pictures, reeling off the multiple bands his musicians had played in, how he’d jammed and toured with them. He radiated while reminiscing about Mika Scott and him performing, as a duo for five years, “a lot of exotic percussion material.”

But he admittedly was skittish about segueing into bandleader and producer.

“All of a sudden,” he said, “I’m doing the calling, the hiring — in the past, I’ve always been called.”

Obviously, everything worked — after having dreamed “for 10 or 15 years” about cutting loose like that and creating a fresh “vehicle for expression.”

Nowadays, most of his gigs lean heavily on jazz. Upcoming dates include Jan. 18, when his trio will play for the annual 6-9 p.m. “Art from the Heart” auction at the Sonoma State University art gallery; Jan. 19, when his jazz quartet will be playing at the Sleeping Lady in Fairfax from 6:30 to 10; and Feb. 10, when the jazz trio will be at the Panama Hotel in San Rafael.

Being the main man has been a huge shift.

Dave had worked as a sideman himself for five decades, having others (such as Joe McDonald of Country Joe and the Fish, with whom he did two extended tours) “tell me what to do.”

He’d also worked solo — as a painter (after having earned a master of fine arts degree and won a Fulbright), despite unfounded fears that his red-green colorblindness would be discovered.

To be honest, it had felt odd watching his bandleader gland throb; I was used to him being mellow.

I was used to him gabbing breezily about yesterday (including getting his first musician’s card more than 50 years ago, at age 15), not tomorrow.

The stickman’s never been shy about his immersion in a historic cliché — sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. But lately he’s been cutting down on his globe hopping with Big Brother.

The road’s not so easy anymore.

And Dave — who still stays fit by climbing the 88 steps of his Ross Valley home (the same number as piano keys, which he also noodles with) — is always the realist. He accepts, in fact, that he’s “known as a ’60s rock musician and my epitaph will be ‘The drummer who played with Janis Joplin.’”

He also accepts that after all those rock gigs, his hearing isn’t what it used to be.

Dave also knows, though, that he still “can play a lot of styles and cover a lot of people.”

And, clearly, more than one instrument.