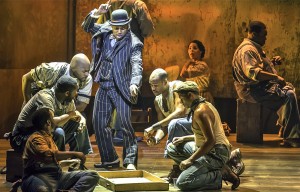

Andrew Durand and Patrycja Kujawska fill the title roles in “Tristan & Yseult.” Photo by Steve Tanner.

Expectations can be killer, especially high ones.

I often find I like performances better when anticipating less. So I was slightly worried about attending “Tristan & Yseult” at the Berkeley Rep.My hopes had been dialed up to max.

It was, you see, a revival from Kneehigh Theatre, Cornwall creators of “The Wild Bride,” an earlier Rep spectacle I’d found thoroughly enchanting. Charming.

And unadulterated fun.

Regretfully, my trepidation about “Tristan” was justified.

It definitely incorporates elements that are wonderful, in both the delightful and filled-with-wonder senses of the word.

And like “Bride,” it’s an amalgamation of music, comedy, dance, ingenious staging and passion.As stunningly surreal as a Dali painting magically come to life.

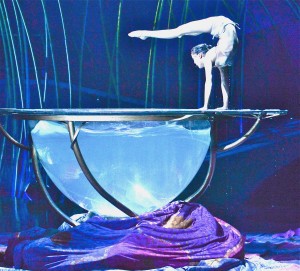

It also dabbles in acrobatics and simulated sex.

But its major problem is being way overladen with gimmickry (such as a carnival-like “love-ometer”). The cornucopia of theatrical tidbits can become extremely tiresome.

Some of the humor, moreover, is veddy British and may be difficult for Americans to absorb — though the accents can easily be discerned.That said, “Tristan,” is a mesmerizing, one-of-a-kind two-hour funny melodrama with a sad worldview that unleashes the story of an adulterous affair. It bursts with all the inherent, predictable dangers of a love triangle.

And, just for spice, it stirs into the concoction a love potion both toxic and intoxicating.

Emma Rice imaginatively adapted the play from a Cornish myth dating to the 12th century. She also directed it. The book, by Carl Grose and Anna Maria Murphy, is fantastic, in both the fanciful and incredible senses of that word.

And music by Stu Barker (played by a quartet under the direction of Ian Ross) runs the proverbial gamut — from country & western to jazz and Latin rhythms, from rock to classical.

The ensemble cast of eight can fairly be labeled (you can pick the appropriate word, or all of them) splendid, excellent, inspired.

Cornish King Mark (Mike Shepherd, Kneehigh’s founder) rules with his brain until he falls from a distance for his enemy’s sister, Yseult (Patrycja Kujawska, who also starred in “Bride”).

She not only becomes the king’s wife but the lover of Tristan (Andrew Durand), a buff warrior and Mark’s neo right-hand man.

Add to that mix the exaggerated Frocin (Giles King), Mark’s psychotic henchman, and Mistress Whitehands (Carly Bawden), part-time narrator, part-time singer, part-time part the story.

Finally there’s Craig Johnson, who splits his time cross-dressing in a chiefly comic role as Brangian and an understated one — Yseult’s brother, Morholt.

Most fascinating, though, is the morphing of male performers into balaclava- and anorak- and horned-rim-glasses-wearing Everyman “lovespotters” who often peer at the world through binoculars. Their buffoonery (and use of bird and other stick puppets) contrasts with their slick knife-fighting choreography and mock brutality.

In effect, they form a modern-dress Greek chorus that occasionally dons floppy headdresses with crushed tin cans and various other amusements.

“Tristan” is a show filled with tension, drama, rhyming verse and Monty Pythonesque hijinks — including an audience release of squealing balloons and a shower of small proclamations containing threats of exile or death.

Plus exciting lighting by Malcolm Rippeth, sonorous sound effects by Gregory Clarke, and a nifty set by Bill Mitchell.

“Tristan & Yseult” was the show that made the fledgling Kneehigh troupe’s reputation a decade ago. The myth on which it’s based, not incidentally, is a forerunner to the legendary triangle of King Arthur; his Queen consort, Guinevere; and Arthur’s main knight, Sir Lancelot.

If you want the ultimate tragic version of the Tristan story, you might want to skip this production and to seek out, instead, a production of Richard Wagner’s epic opera, “Tristan und Isolde.”

I’d suggest, though, that you ignore any expectations you believe I’ve set up.When all things are considered, it’s actually a no-brainer:

If you enjoy “different,” go.

“Tristan & Yseult” plays at Berkeley Rep’s Roda Theatre, 2015 Addison St., Berkeley, through Jan. 18. Night performances, 8 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays, 7 p.m. Wednesdays and Sundays; matinees, 2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. Tickets: $14.50 to $99, subject to change, (510) 647-2949 or www.berkeleyrep.org.