Woody’s [rating:5]

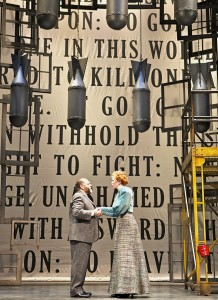

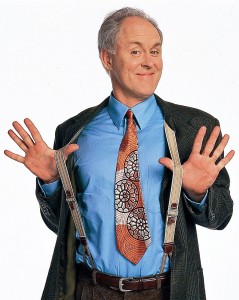

David Yen stars as Capt. Stanhope (right) in “Journey’s End,” supported by (from left) Francis Serpa, Stephen Dietz, Sean Gunnell and Tom Hudgens. Photo by Robin Jackson.

“Journey’s End” is no “War Horse.” I saw no fantastical puppets.

“Journey’s End” is no “Apocalypse Now.” I heard no Wagnerian explosions or deafening helicopters.

“Journey’s End” is no “Saving Private Ryan.” I witnessed no gore.

What I did find, however, was considerable poignancy and a tough look at what war does to young men.

Regrettably, it mirrors the many wars across today’s globe.

It’s an exceptional anti-war drama, despite playwright R.C. Sherriff’s insistence — according to director James Dunn — that he didn’t set out to create that type of play.

It’s also the best Ross Valley Players show I’ve ever attended, and that’s saying a lot because I’ve seen many of their shows that were superb.

“Journey’s End” is a saga of disposable lives in the so-called Great War.

Its setting is a 1918 WWI British infantry dugout/bunker near St. Quentin, France, that’s about to be assaulted by German soldiers (“the Boche”). Its twin focus is on the interminable waiting (which may portend death) and a rushed 12-man patrol sent out to seize an enemy warrior.

The protagonist is Stanhope, a captain who drinks a lot to deaden the pain caused by the conflict and his fears that his men don’t respect him.

David Yen brilliantly portrays Stanhope, who originally was played by a young Laurence Olivier. Yen’s facial expressions and eyes become transparent windows to his character’s tormented soul.

His stage bouts with half a dozen bottles are neither over-the-top nor maudlin.

Yen is impressively supported by Tom Hudgens as Lt. Osborne, an ultra-proper officer who’s purposefully morphed into a kindly uncle to the soldiers, and Francis Serpa as 2nd Lt. Raleigh, a young, idealistic ex-school chum of Stanhope who’s stuck in hero-worship mode.

The rest of the all-male cast also is convincing: Philip Goleman as 2nd Lt. Hibbert, a cowering whiner; Sean Gunnell as Pvt. Mason, comic relief as a cunning kitchen worker always scrambling to make up for supply deficiencies; Stephen Dietz, Jeff Taylor and two actors who each assume dual roles, Steve Price and Ross Berger.

Special tribute must go to Dunn and his assistant dialect coach, Judy Holmes, for training the nine actors so well each accent stayed authentic throughout.

And never turn into caricature.

Deserving extra compliments, too, are Ron Krempetz for his set design (from real dirt on the floor to a hint of barbed wire peeking through an opening); Dietz for his sound design (crackling armaments getting closer and closer yanked me right into the action, and scratchy recordings of “Mademoiselle from Armentières” and “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” became instant time machines); and spot-on costumes by Michael A. Berg.

The two-hour play, despite having first been staged in 1928, miraculously avoids the clichés of the hundreds of war dramas, films and teleplays that came after.

There’s no token black, no token Latino, no token Jew.

There’s no super-patriot, no Dear John letter, no townie with a heart of gold.

Most importantly, there are no heroes.

There are, however, little touches that work especially well to break the tension — the awkwardness of a Brit and German trying to scale language barriers, the reading aloud of passages about the walrus and cabbages and kings, and a bizarre description of an earwig race.

By sidestepping most stereotypes and zeroing in on the human condition, Sherriff, who’d won a Military Cross after being wounded in the battle of Passchendaele in 1917, penned a play with multiple layers that retains its meaning almost a century later.

It won a 2007 Tony for best revival.

Dunn now has breathed new life into it by bringing to the production a rich history of directing and teaching theater arts for 50 years, including three decades at the helm of the Mountain Play.

Is war hell?

In the WWI battle of the Somme, 21,000 British soldiers died on the first day, and 38,000 more became casualties. Mankind apparently didn’t learn much from that episode.

Unfortunately, neither “Journey’s End” nor a multitude of anti-war tracts since have had the power to change anything.

“Journey’s End” will run at The Barn, Marin Art & Garden Center, 30 Sir Francis Drake Blvd., Ross, through Feb. 16. Night performances, Thursdays at 7:30, Fridays and Saturdays at 8; matinees, Sundays at 2. Tickets: $13-$26. Information: (415) 456-9555 or www.rossvalleyplayers.com.