Woody’s [rating: 2.5]

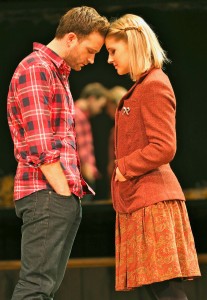

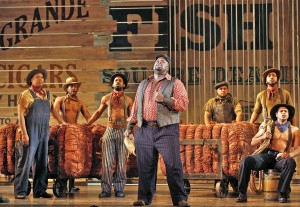

“Woman” (Annette Roman) manhandles the title character (Adrian Ramos) in “Andrew Primo,” a highlight of Fringe of Marin. Photo: Gaetana Caldwell-Smith.

Edgy, electrifying, out-of-the-box mini-plays.

That’s what I’ve eternally hoped to discover at fringe festivals.

Typically, I’ve been disappointed.

I was surprised, therefore, to find a five-playlet Fringe of Marin program mostly satisfying in spite of it leaning heavily on conventional theatrical forms.

Its playwriting, acting and directing generally were a notch better than I’d expect on any campus.

The festival is over now, but you might seriously consider going to the next one.

My favorite piece in Program One at Dominican University was “Andrew Primo,” a lighthearted look at relationships in a phantasmagoric world populated by speed-dating devotees, androids and horny women.

Writer-director Gaetana Caldwell-Smith cleverly utilized her 20-20 satirical eyes to amuse me.

Thoroughly.

And that was sandwiched by two noteworthy shorts — “Fourteen” and “Fighting for Survival” — well-crafted by a lone playwright, Inbal Kashtan, and well-staged and well-paced by a single director, Jon Tracy.

“Fourteen” was a serious look at a self-starving, self-imprisoned teenage girl plagued by the absence of her mother and hospitalization of her cancer-ridden dad.

Stefanée Martin, a young actor with exceptional promise, used nearly every muscle in her face and body to depict her torment as Annie, a girl who makes prank phone calls and convulsively whips off one T-shirt after another to the click-clack beat of time passing.

“Survival” spotlighted the first-rate acting of Sarah Mitchell as a dying lesbian, Maya, and the comic exuberance of Lucas Hatton as Brent, a wilderness census-taker.

And it deftly shifted tone from slapstick to solemnity.

Gina Pandiani, managing artistic director, confided that “what Fringe of Marin’s all about for me is developing young talent.”

She’s already taken giant steps toward meeting that goal, quite a feat considering she’s been at the helm only since shortly after the 2013 death of 88-year-old company founder Annette Lust.

Moreover, she’s been flourishing without needing to embrace wild experiments.

This marks the festival’s 18th year (although, because there are annual spring and fall versions, it’s also its “33rd season”).

Opening night, I was quickly able to determine that the double-program festival provided lots to praise — even when the slightly uneven hour and half of vignettes (that ranged from under 15 minutes to about 35) didn’t quite jell.

And I was a virgin attendee.

Regulars, I suspect, became regulars because of Fringe of Marin’s quality.

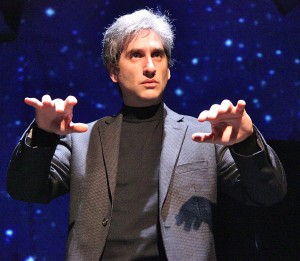

Case in point: “Little Moscow,” the last show in Program One (and the sole reprise for the five-play second), which consisted of a long soliloquy about anti-Semitism and a man tattooed as a traitor because he dared criticize Russian life.

It could have been terrific if only…

• The rich, accented voice of Rick Roitinger — who squeezed every possible emotion from the Aleks Merilo-penned play as a reminiscing tailor — hadn’t sometimes gotten lost in the cavernous Angelico Concert Hall in which no microphones were evident.

• The actor’s voice hadn’t also been overwhelmed by recorded background music (that nevertheless helped the piece’s moodiness with — in rapid succession — melancholic, dramatic and sentimental strains).

• The poetic, sensitively written piece in which Roitlinger starred didn’t feel longer than a Russian winter.

“Pre-Occupy Hollywood,” an amateurish glimpse of Tinseltown as background film actors view it, forcing them momentarily to contemplate a revolution, was the weakest link in the evening.

And it was tolerable.

Opening night drew only 40 appreciative, supportive theatergoers, and that’s a shame because Fringe of Marin clearly merits vastly bigger crowds.