Woody’s [rating:3.5]

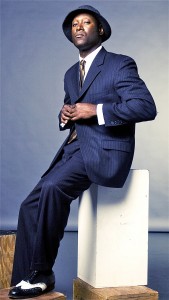

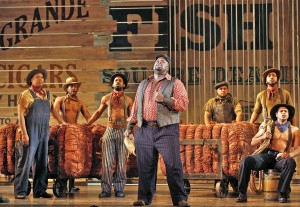

Morris Robinson (Joe) sings “Ol’ Man River,” with chorus behind him, in “Show Boat.” Photo: ©Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera.

As a young buck, I’d often catch performances at the New York City Opera or the Met.

Embarrassing to admit, my tastes ran to the ultra-popular.

I’d see “Carmen,” “Figaro,” “Madama Butterfly” and “Rigoletto” and the like — again and again.

And if someone hinted I substitute part of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle, or experimental compositions such as Alban Berg’s “Lulu” or Dimitri Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of the Misensk District,” I’d recoil.

Then, a budding love of jazz replaced opera in my entertainment life.

Almost entirely.

But seeing “Show Boat,” the new, panoramic San Francisco Opera production, makes me want to re-think my predilections.

And even venture beyond opera’s Top 10.

“Show Boat” certainly isn’t opera — and not truly an operetta either.

But it compares favorably with many of both when discussing spectacle, especially considering Paul Tazewell’s multi-hued costuming and Peter Davison’s resourcefully mobile sets.

And the musical’s 60-plus performers.

Happily, no one bumps into anyone else — unlike an opera I saw not long ago in Vienna, where the stage was so crowded by supernumeraries none could move.

To me, the most satisfying takeaway from “Show Boat” is the historical perspective it offers.

Followed by Bill Irwin’s antics.

The musical about life on the Mississippi had expanded theatrical parameters in its 1927 debut by introducing seriousness to Broadway houses that were previously rife with Ziegfeld’s “Follies” and similar girlie shows, implausible operettas or thoughtless musical comedies.

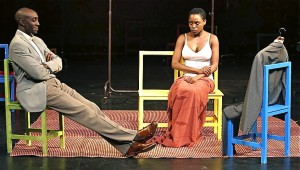

It may seem tame today, but “Show Boat” also confronted racism and miscegenation then by injecting an interracial love story.

Merely providing a storyline, in fact, broke new ground.

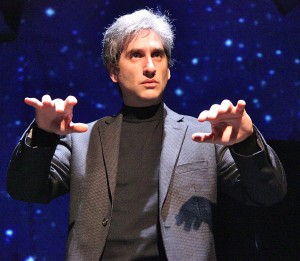

As for Irwin, the Tony Award-winner plays Andy Hawks, the floating theater’s captain, and steals every scene he’s in by stretching his rubber-ish body in ways that ensure all audience eyes stay on him.

This marks Irwin’s second San Francisco Opera appearance. His first was in “Turandot” as an acrobatic, when he was with the Pickle Family Circus.

Two more comic “Show Boat” sensations are Kirsten Wyatt as Ellie Mae Chipley and Harriet Harris as Parthy Ann Hawks.

Wyatt uses her squeaky voice as a laugh-inducing tool, much like the one Kristin Chenoweth rode to fame in “Wicked,” and Harris utilizes a gruff persona not unlike that of Bebe, the agent-manager she played on TV’s “Frasier.”

Some of Jerome Kern’s old-timey music (and Oscar Hammerstein II’s lyrics) may be as familiar as modern-day hits by Andrew Lloyd Webber. Tunes such as “Ol’ Man River,” “Can’t Help Loving’ Dat Man” and “Make Believe.” Others (“Hey, Feller” and “Dance Away the Night,” for instance), I don’t remember hearing before — despite seeing the show in New York years ago.

“Ol’ Man River,” of course, is a tune nearly everyone walks out singing, humming or whistling.

Few know it became Kern’s good luck charm. He purportedly played it each time he left for a trip.

And again when he returned.

Few also know Hammerstein’s wife claimed it was “my husband who wrote ‘Ol’ Man River.’ Jerry Kern only wrote dum-di-dah-dah, di-dum-di-dah-dah.”

At the revival’s opening, several white-haired theatergoers equated Morris Robinson’s show-stopping “Ol’ Man River” to those of James Earl Jones and Paul Robeson.

More strong voices?

Check out the soprano tones of Heidi Stober as Magnolia Hawks, and baritone Michael Todd Simpson as her suitor, Gaylord Revenal.

Musical director John DeMain blends everything as smoothly as a perfect gimlet.

But let’s not ignore the dancing in “Show Boat,” a co-production with Lyric Opera of Chicago, Washington National Opera and Houston Grand Opera.

It’s dazzling.

Choreography by Michele Lynch shrewdly melds old hat with a touch of modernity.

David Gockley, company general director (who previously staged “Show Boat” in 1982 and again in 1989 with the Houston company), says the new production is “the way the creators conceived” it. While director Francesca Zambello notes the original show employed a black and white chorus in an era when black cast members couldn’t even have their own families in the audience.

“Show Boat,” remember, trail-blazed the way for George and Ira Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” — and countless other musical works.

In a sense, though, it’s like a treasured 1927 photo album brought to life.

“Show Boat,” which runs in repertory with “La Traviata” and “Madama Butterfly,” will play at the War Memorial Opera House, 301 Van Ness Ave. (at Grove Street), San Francisco, through July 2. Tickets: $24 to $379 (subject to change). Information: www.sfopera.com or 864-3330.