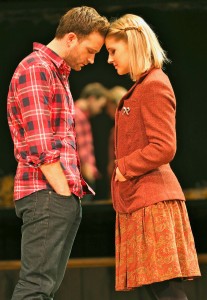

Patrice Hickox sits on memorial bench in Bolinas Park in Fairfax that she fought to get installed. Photo: Woody Weingarten.

Patrice Hickox would prefer I think of her as ordinary.

She isn’t.

The Fairfax resident’s a real-life Energizer Bunny.

Without floppy ears.

A perpetual motion machine with platinum-hued hair and hands that intermittently sketch pictures in thin air. A do-gooder everlastingly battling for one cause or another.

Since I’ve tilted at a few windmills myself, I like that.

Still, no matter how much she achieves, she’s never able to rest on her laurels.

She is resting one recent Saturday, however, on a memorial bench at the edge of Bolinas Park in Fairfax she fought hard to get installed at the end of May.

Not quite relaxed.

Trying to figure out how she best can help Marin’s foster children keeps her mind flashing like a July 4th sparkler.

She can’t know a Marin County Civil Grand Jury will shortly issue a report saying more funds must to be spent on the issue, more communication must occur between foster parents and social workers, and more access to therapy must be provided those neglected kids.

What to do? What to do?

She and I are together, me armed with interview pad and pen, she momentarily staring off into the distance at a bald hill she knows must be preserved.

Of course.

One cause at a time isn’t her style.

She’s also thinking about finding a way to replace “the dingy, worn-out, style-less sign announcing the Town of San Anselmo.”

And improving local median strips.

How?

“Re-plant, re-think, re-design,” she tells me.

The artsy wood bench we’re on is dedicated to the memory of her friend, Nancy Helmers, an environmental activist who died last year at age 82.

Patrice tactfully declines to reveal the political obstacles — “the kerfluffle, the brouhaha” — she had to vault to make it happen.

She’s just glad it’s a done deal.

Nancy had served on the county’s Open Space Committee for 10 years, as well as many other boards, and had been as non-stop energetic as Patrice.

She also was an unrelenting firebrand when it came to pushing petitions. “No one could collect a signature like Nancy,” Patrice tells me. “No one would say ‘No’ to her.

The two women met in 1988 when Nancy was collecting names in favor of creating a multi-purpose park on the 28 acres of the Marin Town and Country Club, which was being eyed by a developer.

The pair stopped the development from happening.

But they couldn’t come up with an effective plan to raise enough money to build their dream park.

“Instead, we became friends,” Patrice remembers. “We were both birders and environmentalists. We hiked, and we eventually collected thousands of signatures for a lot of things that failed.”

There were, however, sporadic triumphs.

Such as Lansdale Park in San Anselmo, a pocket-sized space with a children’s playground — or, as the town’s website says, “just what the neighborhood needed! Parents can enjoy a coffee-to-go from the nearby café while watching their children play outdoors.”

Patrice recalls “they were going to put condos there, but we got a petition to stop it. We got two grants from the Buck Fund, and got students from the White Hall Middle School in Fairfax to help. It was great.”

Her awareness began shortly after reading Rachel Carson’s best-selling “Silent Spring,” which detailed the detrimental use of pesticides.

“I was off and running after that,” she says. “I stopped eating meat and started paying attention. I was 14.”

As a Manhattan teenager, she’d attended be-in’s in Central Park, marched in Washington against the Vietnam War, and rallied for civil rights.

“I guess I’ve been a die-hard liberal ever since I figured out what that was,” she says.

Sometimes Patrice, who’s lived in Fairfax since 1995 with Charlie, her musician husband of 41 years, volunteers longer than she’d intended.

She helped out at WildCare for more than 10 years, for instance, “raising hundreds of baby things — from snakes to foxes to raccoons and squirrels.”

If she could accomplish anything in the world, what would it be, I ask. She replies without hesitation: “Get rid of Putin and Assad.”

Then she says, “I think I’d like to be empress of Oakland and just fix that city.”

And then, after a slight pause, she adds seriously, “Anything that I’d be effective at — so I wouldn’t have to beat my head against the wall again.”

I smile.

Since I’ve tilted at a few windmills myself, I understand completely.

You can contact Woody Weingarten at voodee@sbcglobal.net